Eve here. My rewrite headlines to Voxeu’s work (originally the risks of a new international trade environment) may seem surprising, but even the opening paragraph shows that they are leaving the risks that have been going on for so long as if they were new developments. The reason for presenting this article is that it includes useful analyses such as the concentration of imports of certain high-tech products that are particularly dominant, difficult to exchange, or that give a much more important feel to their role.

Nevertheless, this post illustrates here the seeming danger to neoliberal doctrine that liberalised trade solves all problems. During my high school discussion, I came across a serious polyjournal article about the United States (IIRC), which relied on certain countries in Africa for major minerals (again, IIRC, geopolitics of certain exporters did not reduce it.

by Florencia Aired, the Federal Reserve Economists’ Commission on Government. Francois de Soyres, Chief of the Federal Government Commission for Advanced Foreign Economics. ECE Fissal, Board of Directors of the Research Federal Reserve Committee. Alexandre Gaillard, postdoctoral researcher, Julis Rabinowitz Public Policy & Finance Princeton University Centre. Anna Santacle of the Reserve Bank of St. Louis’ Economic Policy. Keith Richards, Federal Research Assistant Reserve Government Commission. Henry Young, a doctoral candidate for the University of Michigan. Originally published on Voxeu

Earth trade is entering a new era shaped by geopolitical alignment and the evolving role of China. China You are becoming a direct competitor of the high-tech sector while thwarting important input markets, creating double risks in the form of supply dependence and industrial evacuation. These risks are increasingly strengthened against each other, making traditional trade logic difficult. This column documents these shifts using new data on trade flows, technology overlap, and input concentration. This highlights the strategic vulnerabilities facing senior economies, particularly in Europe, as trade becomes more politicized.

As developed countries rethink supply chain security and industrial resilience, international trade enters a new stage, driven less by efficient and strategic logic. Three simultaneous forces are transforming trade. Selective geopolitical fragmentation, rapid technological rise in China, and its advantage over rare earth and other important inputs (Alfaro et al. 2025).

The growing literature shows that trade patterns increasingly reflect foreign policy alignment (Gopinath etal. 2024, Goldberg and Route 2025, Airaudo etal. 2025). This column builds on the broad outline of trade fragmentation and initial insights to examine the risks poses of China’s evolving role for the outlook of an advanced economy. It particularly highlights how industrial competition and input dependence strengthen the strategic vulnerability of developed economies.

Although we have not advocated any subtle trace policies, the ORT’s goal is to provide a positive analysis of recent changes in global trade. In principle, a world with minimal trade friction – efficient and comparative advantage guide trade flows will strengthen welfare, but recent developments suggest an increasing role for strategic considerations.

Geopolitical Selective Fragments

Geopolitical alignments are increasingly shaping trade flows, but patterns are selective and China plays a unique role. To quantify geopolitical distance, we use the ideal point distance (IPD) based on how closely the country’s voting patterns are lined up (Bailey et al. 2017, Airaudo et al. 2025). Using 1 geopolitical distance, based on all votes, we estimate the impact of STIs on both side trade using a standard gravity framework, using a 10-year rolling window and controlling traditional trade.

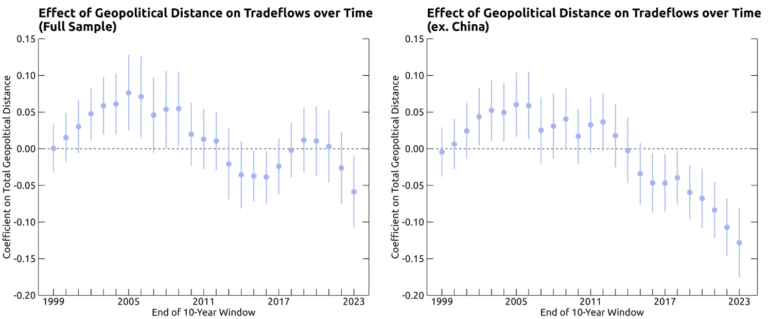

The left panel in Figure 1 shows the geopolitical distances you began to weight trade despite the moderate effect. Except for China (right panel), the correlation is much stronger. This reflects China’s unique behaviour to broadly expand exports while significantly reducing imports, attenuating the overall link. This suggests that fragmentation is authentic but uneven, and that China hides a fundamental shift. It is also sector-specific. In Europe, fragmentation is concentrated on low-tech good. The high-tech sector is more affected in the US.

Figure 1. Relationship between geopolitical distance and trade flows

>

China’s rising competition

China is becoming a more competitive, asymmetric trading partner in the developed economy. To support how trade competition is evolving, we rely on partner similarity index (PSI). This quantifies how well the specialization of the exporter sector matches the demand of the importer sector (De Soyres et al. 2025a). Inspired by the similarity index introduced by Finger and Kreinin (1979), PSI values range from 0 to 100, with more numbers indicating stronger sector alignment.

Figures 2 and 3 show that PSI between China’s exports and advanced economic imports is steadily increasing, especially in sects such as mechanical, electronics and transport equipment. This shows that while China once specialised in cheap, low-tech products, it is now increasingly supplying advanced products types that hinder the movement of the value chain and transition to production-complete rivals.

At the same time, PSI between advanced economic exports and Chinese imports fell. In particular, exports in the Euro area are not very consistent with those purchased by China, particularly in the automotive sector. This difference highlights China’s efforts to become more independent in the strategic sector, as documented in Soyres and Moore (2024).

Figure 2 Similarity between the Euro Region and China’s sector trade

Figure 3Similarity of US and China’s sector trade

These trends show not only increased global competition, but also increased asymmetry. Although developed economies are exposed to China as suppliers, China does not rely on them as an existing trade imbalance that will allow markets between Western countries and China to exist.

Catch up innovation

China has shifted from cost-based competition to innovation-driven rivalry in the strategic sector. To understand whether this competitive shift is supported by technical capabilities, we turn to patent data. When inventors and companies file patents overseas – what we call “patent exports” – they are creating a strategic decision that reveals the global ambion. As explained in Labelle et al. (2023), companies usually pursue international patents to ensure exclusive rights to sell innovations in valuable foreign markets.

Figure 4 shows the export similarity index (ESI) calculated using the patent “Export”. ESI provides a measure of future prospects for innovation and tracks how similar the technological output of the two economies is across sectors.

Figure 4 Patent Similarity Index

De Soyres et al. (2025b), found that Chinese patent activities are emerging in major sectors such as communications, green energy, and electronics. ESIs in both China and the US and Euro regions have increased significantly over the past decade, suggesting that China is not only generating what its developed economy demands, but is innovating in the same strategic sector. Taken together, PSI and patent-based ESI analyses show that China has evolved from a partner that sources advanced technology products from overseas to becoming a predominantly independent rival in these sectors.

Strategic input dependency

High import concentrations of important inputs create structural vulnerabilities in developed economies. Figure 5 illustrates China’s dominant role in the refining of important minerals and rare earths. China alone accounts for more than 90% of the world’s rare earth treatments and holds a significant stake in global capabilities when refinement of other strategic materials. These inputs are essential for a wide range of industrial and defense applications and are difficult to replace during the period of shorts.

Figure 5 Global concentrations of important mineral supply chains, 2023

Building on Mejean and Rousseaux (2024), Figure 6 shows that, based on Herfindahl Indes, imports of advanced technology products are highly concentrated in both the Eurozone and the US. Although the details are different, both regions rely heavily on several suppliers (geopolitical far) for important inputs associated with the green and digital transition. This concentration increases the risk of supply disruption due to logistics shocks, trade disputes, or forced police.

Figure 6 Import concentration using Advanced Technology Products, 2023

These vulnerabilities are not hypothetical. In 2010, China reduced its export quota by about 40% in the midst of a maritime dispute with Japan, and suspended its temporary suspension to Japan due to rare earth export restrictions. The move has led to rapid prices rising and disruptions in sophisticated economies, particularly downstream industries in electronics, renewable energy and defense. Recent policy developments suggest that similar restrictions will renovate live possibilities.

Reinforcement risk burst

China’s rise in global trade carries two distinctly interconnected risks in the developed economy.

First, China is directly competitive in the high-tech sector, such as solar, electric vehicles, and telecommunications. As China exports local production, this creates alternative risks. Second, China controls the supply of difficult input rare earth, graphite, and battery materials that create complementary risks. The advanced economy relies on Chinese inputs and becomes vulnerable to export restrictions.

Importantly, these risks enhance each oher. China can simultaneously override foreign production and increase its own market share by limiting critical inputs while offering read-away alternatives. This dual mile expands the strategic vulnerability that links upstream control with downstream advantage. To address this challenge, a coordinated response is required – combine innovation investments, supply chain resilience, and reliable international partnerships.

Focus on Europe

Fragmentation exposes monetary policy to structural risk. Reliance on geopolitical distant suppliers can increase inflationary pressures as the possibility of increased sustained supply shocks and inflation volatility. Strategic fragmentation can also increase the contribution to market concentration, reduced competition and price stickiness. Furthermore, uneven exposure in the Euromirror area province complicates a unified monetary policy response.

Deeper internal integration Coul helps the eurozone respond more effectively to global fragmentation by not only increasing resilience, but also increasing innovation and external competitiveness. Our new estimates suggest that internal trade barriers remain important, from regulatory differences, infrastructure gaps and non-anharmonic standards to years of advancement. Friction regeneration has expanded the scale and efficient expansion of domestic production, helping European companies compete better in the global market. At the same time, more integrated capital markets improve access to innovation financing and support broader risk taking.

Author’s Note: The views in this column are our own and do not represent the views of the Federal Reserve Committee, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, or others relating to the Federal Leelub System.

______