Before the current era of nuclear war unrest, the idea was widespread concern about poison gas, a horrible weapon of mass destruction in the early days. I will explain the history of war gas in the context of our current concerns about the atomic war. It’s an ugly topic, but examining it might provide hope for a way out of our current predicament.

How did it begin?

The origins of chemical weapons date back to ancient times. When Aries first uses harmful substances and smoke to gain advantage in combat. In the siege, defenders and attackers similarly adopted burning sulfur, pitch, or quick lime to create shaking and blind clouds. The famous Byzantine Greek fires, which developed in the 7th century, also had elements of psychological fear and chemical burning, but were more innovative than toxic. However, these early efforts were rudimentary and lacked scientific control.

It was not until scientific advances in the late 18th and 19th centuries that the foundations of modern chemical warfare were established. Pioneering chemists such as Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Humphry Davy have isolated and described diversity in highly toxic gases, including chlorine, phosgene and hydrogen cyanide. You are a substance and are known for their choking and deadly properties, and military thinkers of SOM have begun to consider the potential use of Condidad Esta. During the Crimean War of 1854, the British scientist Lyon Playfair rejected the idea against the norms of the civilised war, but even deployed a division that deployed shells filled with Cacodylcyanide against the Russian army.

The first systematic and large-scale use of chemical weapons came during World War I. With the Western Front in a dead end, Germany turned its eye to the growing chemical industry and the expertise of chemist Fritz, which has to develop new weapons. On April 22, 1915, in the second battle of Ypres, the Germans relayed over 150 tons of chlorine gas from the cylinder, creating greenish yellow clouds floating across Norman’s Rondo and across the Allied ditch. The attacks were killed, and thousands of trees were established, shocking the world. Over the next few years, both deployed climate agents, including phosgene and diphosgene, mustard gases introduced in 1917, including more powerful shaking agents. By the end of the war, chemical weapons had killed more than a million people and left lasting scars in the collective memories of the conflict.

On October 15th, 1918, a few weeks before the armistice, Adolf Hitler was in the physical service of the Bavarian Reserve infantry regiment. That day, troops near Ipress in Belgium were hit by British mustard gas attacks. Hitler reported suffering from temporary blindness and lung irritation from exposure to gas clouds. He was evacuated to a military hospital and he was still recovering when Germany signed an armistice on November 11, 1918. Hitler lately fed his postwar political ideology.

Chemical Society

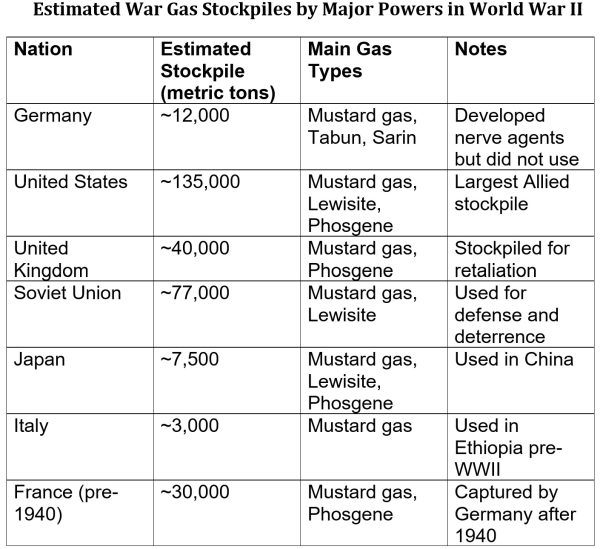

During the interwar period, there was a widespread view of the chemical warfare and implications of the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which banned the use of chemical weapons. However, research continued in secret, and the nation stockpiled mustard gas, phosgene, and newly discovered nerve agents such as Takun and Sarin, which were developed in Nazi Germany in the 1930s.

World War II was much more destructive than World War I, but war gas was not used in theaters in Europe or the Pacific. The reason for this was the fear of retaliation. Allied forces and axial forces had gathered a significant inventory of chemical weapons that served as decisions. The exception to this standoff was the use of Japanese war gas on Chinese military and civilians from 1937 to 1945. China had no white gas weapons.

The history of chemical weapons reflects the tension between scientific advancement, military innovation and ethical restraint. What began when crude battlefield smoke evolved through industrial and scientific advances into the submission of the most feared modern war weapons, spurred both fearful and international efforts to control the use of ESIR. Public disgust and international diplomatic efforts ultimately result in a comprehensive treaty banning chemical weapons.

Final agony

The use of poison gas in the war did not end completely after World War II, but the great powers gradually abandoned such weapons due to boredom, treaty restrictions and operational restrictions. Chemical weapons were used sporadically in regional wars, which were recognized by warriors. The post-toxic gas use after World War II was due to Iraq in the war with Iran, but the weapon was not strategically critical. Weapon technology has increasingly targeted accuracy through the munit of regional effects, which further reduces the usefulness of internationally banned weapons.

From poison gas to radioactive fallout

The evolution of nuclear weapons continues with courses parallel to the course of chemical weapons. Over the years following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the nation has accumulated a large arsenal of weapons, which are so horribly devastating that it has not yet been used. This balance of fear entails diplomatic efforts to mitigate danger by limiting the size and composition of nuclear weapons through the Arms Control Treaty.

Historical similarities extend to the lives of Fritz Ha and J. Robert Oppenheimer. Both were outstanding scientists in their field, directing their talent towards weapon design for patriotic reasons.

Growing up in a Jewish family, HA believed that his work in the major development of war gas in World War I would spare him from persecution under the Hitler regime, but he was effectively expelled from his honorable position in Germany, which he left with the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in 1933. We have significantly expanded our fertilizer and global food supply. The dark legacy of this work on donxigas leads to research that leads to development by others of Zyklon B gas, which will later be used in extinction camps in Germany. Ironically, he died in 1934 while taking on the role of supervision of what would become the Wiseman Institute in Palestine.

Oppenheimer left his outstanding career in physics and led the Manhattan Project. He was motivated by the fear that Nazi Germany would develop nuclear weapons. When Germany was defined, this threat was no longer ruled out, but he did not want to oppose Baste Japan’s use of bombing. He then felt moral unrest and worked to prevent further use of nuclear weapons by advocating international agreements to prevent the arms race. I declared to prevent further proliferation and to make nuclear weapons a political deterrent rather than a military tool. The more devastating potential for the development of hydrogen bombs led the government to strip him of security clearance in 1954. He was kicked out of the inner circle of US nuclear policy, publicly shamed, and created a symbol of the danger of objection during the Cold War.

Conclusion

If the future of nuclear weapons continues to parallel the future of chemical weapons, we hope that the balance of current fears will be concluded by weapons management contracts that will culminate in the nuclear weapons debate. Neithher chemicals and nuclear weapons have not been invented, but their availability and willingness to use them may be effectively limited. Furthermore, steady progress in the effectiveness of nuclear-free weapons promises to meet the defensive military security requirements of countries around the world. The final irony is that the quest for the ultimate weapon self-identifies.