Eve here. The following posts are a compilation of important posts published by the European Investment Bank, which estimated climate risks in 170 countries. Needless to say, this is a variety of important exercises and I hope other experts will try to improve it. Even with the use of a PDF compressor, the proper investigation was too large to embed, but here we find Chan. At the end of this post, I included the juicy parts and the ranking of the country. .

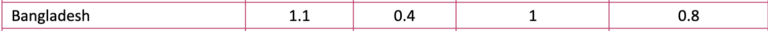

I haven’t read the report in full, but I was surprised at the total survey results for each country ranking. 1 = Global average risk, so higher numbers are bad.

I think the total results will be interesting:

I have cited Bangladesh for nearly 20 years, even in early Pentagon-related reports on the geopolitical risks of flood-induced climate change mass migration. This has been confirmed by LSE in a 2023 paper.

Almost 60% of Bangladesh’s population is exposed to higher flood risks for the greater population than any other country outside the Netherlands, with 45% being the world’s highest river flood risk exhibit.

Also consider:

Huh? The UK is not even self-sufficient in its foods. Frequent flooding and unexpected heat waves have further reduced farm production. We posted that British dairy farmers are using grains they were planning to use for feeding this winter because they are unable to graze them. At the beginning of the week of farmers, the BBC faces a crisis as drugs fail:

Dairy farmers are in danger, spending thousands of pounds on cow grain that should be saved for the winter.

This year’s long dry spring – the warmest and most sunshine on record – you have been forced to make many farmers unprecedented behavior.

Sarah Godwin, a dairy farmer in North Wiltshire, had to feed her cows for the first time in her life. She said, “I didn’t know about these seasons, the heat, the lack of rain, and I had no idea for a long time.”

“The grass is completely exhausted,” explained Mrs. Godwin.

“It’s not good. It has no nutritional value at all and is completely sturdy.”

I have not read the methodology carefully, but a quick search did not show any reference to “food” in the main text (the references that included “food security” in the title only had one paragraph with the word “water.”

This sem will become the source of armor spots about the poor who feed on populament.

To quantify the impact of climate change, we first collect structural information on the economy (e.g., agriculture, population economic contributions) and climate-related information (sea levels rise in temperature, population share). We usually rely on empirical research and academic literature results to turn data into economic impacts. Finally, adaptive capabilities expressed as percentage points of GDP are also explained. Various physical risk factors are explained below, underlying variables are shown in Tables 1 and 2, and Appendix A.1 contains methodological details.

Therefore, focus SEM ensures that it fully extends to economic impacts rather than broader survival.

That may be explained before the evaluation:

But this score makes intuitive sense:

Uruguay You have produced almost all of your electricity from hydroelectric power (but the water rarity has a long end of total risk). It’s not only a food is self-sufficient, but it’s a big export given its size. It was very high on my list of potential foreigners as it is well located in light of climate change.

Matteo Ferrazzi, Senior Economist European Investment Bank, Fotios Kalantzis, Senior Economist European Investment Bank, and Sanne Zwart. Originally published on Voxeu

Climate risk lies at the “code red” level across humanity, urging investors and policymakers to focus not only on risk, but also on strategies that strengthen opportunities and climate change rebuttals related to green transitions. This column presents new climate risk scores for over 170 countries, distinguishing between physical and transition risks. The scores reveal that emerging economies and developing countries are most exposed to physical risks, primarily due to physical events, rising levels and high temperatures in ACTE. Transition risk is relays in fossil fuel producers and wealthy countries.

Interest in national climate risks has increased in recent years, particularly in the years following the 2015 Paris Agreement, outlining clear decarbonisation pathways in each country. Investors are also gradually aware of the long-term risks of climate change. Indeed, exposure to physical climate risks can have negative implications for sovereign debt (Zenios 2022, Bernhofen et al. 2024), the costs of valuing debt and sovereignty (Beirne et al. 2021, Standard & Poor’s 2015, Aga. Rovollalaet al. (Semeniuk et al. 2020).

In practice, three broad approaches are used to assess climate risks at the national level: modeling, scene analysis, and (index-based) scores. Multidimensional macroeconomic models aim to assess the macro impact of climate change. Submarine organizations regularly develop Offen based on model output, sketching multiple plausible (rather than prediction) future representations under various policies and circumstances. Generally, scenes like this project the future consequences of climate change over the long term (60-80 years from now). In addition to modeling and scenario analysis, index-based scoring can help assess climate risks and ranked countries (e.g., Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND Gain) and German Airlines). Evaluation agencies began to develop their own assessments to complement their assessment methods (Volz etal. 2020, Gratcheva etal. 2020). Typically, they combine environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards to help investors create reported investment obstacles.

New Climate Risk Country Score

A recent paper (Ferrazzi etal. 2025) presents an index to measure climate risk in more than 170 countries, assessing physical and transition risks separately (compared to the size of the economy compared to other countries) and assessing mitigation capabilities separately. The most relay risk factors are carefully selected, and the relevant weights are assigned based on literature and empirical evidence. The physical risk score combines the following:

Acute risk: Damages from extreme weather events based on historical realization (compared to the proportion of GDP and therefore the size of the economy). Chronic risk: Agriculture, sea level rise, impact on infrastructure, heat and water shortages on labor productivity (as a percentage of GDP). The economic capacity to respond to shocks and adaptability based on the national institutional capacity (tax ratings, prosecutors of respect, government indicators).

This approach automatically provides the relative importance of each risk factor in each country based on mitigating the impact as a perpetual GDP, and solves the problem of finding the appropriate weight.

Transition risk scores reflect the performance of countries in the past, today and near future.

A commitment to mitigate CO2 emissions and emissions. Fossil fuel rents from coal, gas and oil (as percantate of GDP); renewable energy deployment (excellent in final energy consumption); energy intensity of economic activity; and climate policy ambitions based on nationally determined contributions (NDC) required the Paris Agreement.

(Various) existing rankings use a large number of equal weighted indicators and implicitly assign equal importance to the number risk factors. In contrast, our approach is to select relevant variables, assign appropriate weights, and focus on the period as time for the next 5-10 years. Morover, an unclassified approach that is read only with publicly available data, beyond existing methodologies (e.g., chronic risk of transition risk or mitigation).

Is WHO at the most risk?

Evite Climate Change is at the “Code Red” level of humanity as a whole (IPCC 2021, Guterres 2021), and countries are exposed to different risk intensities. Our climate risk countries scores show that emerging economies and developing countries are most exposed to physical risks, particularly physical events (hurricanes and storms, floods, fires), sea level rise and high temperatures. In general, emerging economies and developing countries are exposed to higher temperatures (as additional temperatures in already hot environments affect human activity) and agricultural losses (which are most dependent on weather conditions). You are also a country that cannot adapt (i.e. to protect yourself from weather efforts). The transition risk is relays of fossil fuel producers and wealthy countries that need to reduce emissions, and Thue countries that are not preparing for a net-zero transition of energy-efficient heat and renewable energy deployments.

Figure 1 Risk factors contribution

Note: Weighted averages by country. The global average of scores (troubling adaptation) is 1.

Figure 2. Physical and transition risks according to countries

Note: The Caribbean and Pacific Oceans (not clearly visible in the map above due to the size of the country) face high physical risks, respectively, and high and elevated transition risks, respectively. The global average of scores is 1 for both physical and transition risks.

Conclusion

Summarying the risks of a country’s climate into a score is a complex task that requires a fierce secret network of objectives, time frames, risk factors, and granularity levels. Suppose some climate change available indicators rely on a number of equally we factors (“as long as you can cover”) and that they are all equally relays. Our climate risk countries scores identify key risk factors and adjust weights based on literature and economic chemistry analysis.

Climate risk scores from 170 countries confirm that climate risk is not evenly distributed. Emerging and developing countries are more vulnerable to physical risk and are escheating the investment in relays to adaptive capabilities. In contrast, transition risks can be seen to be higher in wealthy and fossil fuel producers.

Our national level climate change risk scores have a wide range of uses and meaning. First, as climates evolve in integers and regulatory requirements, banks and international financial institutions can use scores to support the risk management process. In fact, using an early vintage of our score, Cappiello et al. (2025) Climate risk relays, particularly physical risk-confirmation for sovereign credit ratings. Scores act not only as a risk management tool for sovereign counterparts, but also as a starting point for assessing the climate-related risks faced by certain domestic companies and banks.

Second, our scores can also represent opportunities to identify mitigation and adaptation priorities and associated funding to increase climate resilience.

Third, the results highlight the importance of international cooperation as climate change is a broad phenomenon affecting countries around the world and demands collective efforts.

Author’s Note: The views expressed here do not reflect the opinions of the European Investment Bank.

See original bibliographic submission

00 Climate Change Ranking Table