China recently experienced a housing accident comparable to what the US experienced in 2006-10. Before considering the consequences of that housing accident, let’s take a look at what happened in the US.

Between January 2006 and April 2008, U.S. home construction plunged more than 50%. As a result, the crash of the hat continued to go quite well as other sectors picked up sagging. The unemployment rate has risen from 4.7% to 5.0%, but it remains a strong labor market.

In mid-2008, the Fed adopted one of the close moon polys in US history, and NGDP began to decline. Home construction has also declined to a level about 70% below its peak in January 2006. More importantly, other sectors have also begun to decline. The unemployment rate skyrocketed from 5% to 10% of the workforce. It was the first workstroke recession since the 1930s.

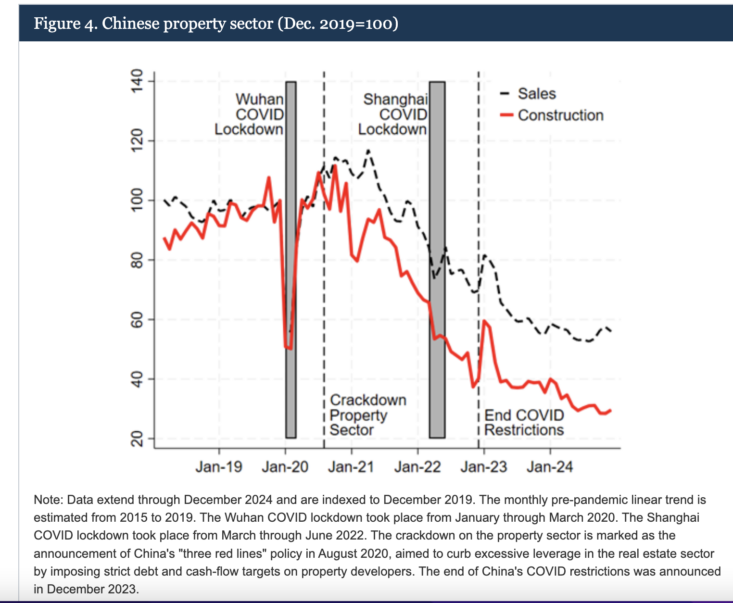

An attractive new paper by Fed economists William L. Barcelona, Danilo Cascaldi-Garcia, Jasper J. Hoek, and Eva Van Leemput shows that China has recently experienced a very similar home construction slump.

In short, it was even more shocking than a housing accident in the US. Chinese property ate cyclical peaks (including indirect effects), which are RATOs, which are much higher than the US, which experienced the housing boom of 2005-2006, about 30% of China’s GDP. The authors seem to find it surprising that China’s GDP growth is maintained fairly well despite severe housing slump for the major sectors of the Chinese economy.

The 5-pecent growth will be much slower than the average 10-person growth that China sustained from the 1980s to the early 2010s, but it could be considered high given China’s long-standing real estate market corrections. Prior to this recession, estimates suggest that the real estate market occurred directly or indirectly for up to 30% of GDP, and official data suggest that real estate and construction activities contributed one or more points of anomaly to GDP growth (Rogoff and Yang Yang, 2024). With the real estate market bubbles burning out over the past few years, that boost has turned into a drag that effectively weighs GDP growth.

3. China’s activity data

What explains strong growth compared to what the property malaise suggests? You can gain insights by examining the total metrics that fall into the model. These indicators show that different parts of the Chinese economy have changed Vray differently in post-pandemic journals.

Panel (a) in Figure 3 shows that while industrial production has significantly disrupted the initial lockdown of Uhan, it exists quickly and, if any, has surpassed the pre-pandemic trends in recent years.

This was essentially what happened in the first two years of housing slump in the United States. The Fed maintained growth in NGDP, and the decline in home construction was primarily offset by surprises such as manufacturing, exports, services and commercial construction.

I have in recent years claimed that Ben is too evacuated to that monetary policy. Nevertheless, the PBOC is expanding more than the Fed was in the 2008-09 Journal. As a result, China’s NGDP continues to grow, and the entire Chinese economy continues to move forward.

The author works for the Fed, but they did not minify any obvious conditions between how the central bank in China handled the poor housing and how the Fed mishandled our homes. Vaidas Urba discussed the new paper in a recent tweet by Zach Mazlish.

This paper is by Tomás E. By Caravello Alisdair McKay and Christian K. Wolf, this comment includes:

The finding of the heading is that, without the effective binding lower limit of nominal interest rates, poly following the minimization rule (9) is involved in very aggressive interest rate reductions, reducing to about -5%. Such a (interest) speed reduction would significantly reduce the output gap at the expense of moderately rising inflation.

The results are summarized in Figure 9. This is shown as the counterfactual (blue) path of output, inflation, and interstitute, as well as realization (black). As before, the blue regions corresponding to the posterior parts of all four models are very similar in results for all individual models. Our findings are useful for broader policy responses during the Great Recession. Given the constraints on nominal interest rates, politicians have sought to replace them through other stimulating measures, most notably unconventional monetary policy, and fiscal stimulus measures. If we interpret (9) as the objective of monetary policy, our counterfactual suggests that the unconventional financial police breathing was misleading – in the nominal interest rate space, an additional stimulus of about 500 basis points is bothering us.

In a follow-up tweet, Mazlish predicts one of my two reactions (I think the second half of 2007 is a bit too early, but I think it was suitable for ZLB around June 2008):

The second point I made is that a better policy administration reduces the severity of the negative demand shock in late 2008 and therefore the amount of financial stimuli that was poor. For example, a reliable policy of targeting at the NGDP level would have generated stable expectations for faster future NGDP growth after a short slump in mid-2008. This WoOld is based on Paul Kugman’s Seminar 1998, not just my views, but also the advantages of level targeting in academic research by people like Beninque and Michael Woodford.