Propublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates power abuse. Sign up and receive the biggest story as soon as it’s published.

This article is published in collaboration with Texas Tribune, a non-profit, nonpartisan local newsroom that informs and engages Texans. Sign up for Bried Weekly and stay on track to essential coverage of Texas issues.

In a half-empty committee room in late April, one of Texas’ most powerful Republican senators pitched legislation, making it more difficult for the country’s immigrants to illegally obtain employment.

Her bill requires all employers in the state to use a free federal computer system known as e-verify. This will quickly check if anyone has permission to work in the US. Sen. Royce Kolhorst of Brenham has ticked a few Republican-led states mandating programs for all private companies, listing other states that need most of them for a given size. But Texas is proud to be the toughest illegal immigrant in the country, dictating that only state agencies and sexually oriented businesses should be used.

“E-verify is the most functional and cost-effective way that Texas can implement to stop the flow of illegal immigration or to ensure that non-legal people are people who can work in Texas.” (The proposal never reached the Senate floor.)

No one opposed the new law. Only one Democrat committee member questioned, and supporters also asked if they supported the Immigrant Guest Worker program. A small number of workers called the bill a bipartisan priority, and testified that employers were too few and cut the corner by illegally hiring workers at low wages. The bill continued to sail the committee and the Senate.

But then, the law has died, like dozens of electronic testing bills in the past decade.

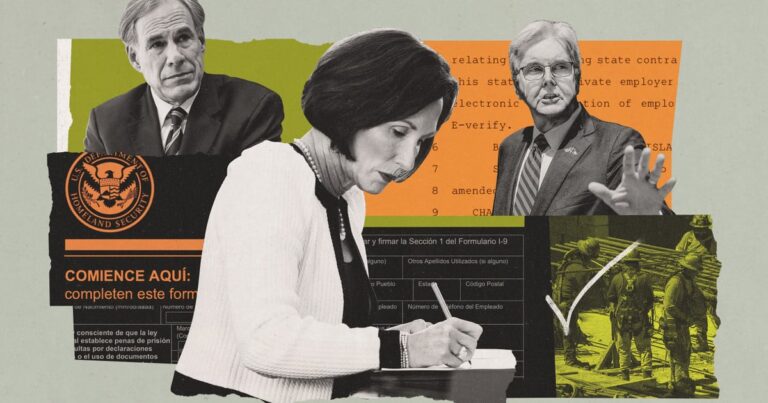

Top Republican leaders in Texas have built a political brand into the state’s strict stance on illegal immigration, and have poured billions of dollars into Gov. Greg Abbott’s state border security initiative. In this session, lawmakers voted to require most sheriff’s offices to work with federal immigration agents.

Once again, the state’s conservative legislature refused to take what some Republicans call the single most important step to prevent immigrants from coming here illegally.

Since 2013, GOP lawmakers in Texas have implemented more than 40 e-Verify bills. Most people tried to request programs for government agencies and their contractors, but about 12 people tried to expand the system to private employers in some capacity. With a few exceptions, including requiring contractors in certain states to e-verify, Republican lawmakers have refused to pass the overwhelming majority of these proposals.

In this session, lawmakers introduced about half a dozen bills attempting to require private companies to use the program. Kolhorst’s legislation was the only law that came out of either legislative room, but eventually died because the Capitol did not take it.

Given the border rhetoric of Texas leaders, it is a “obvious omission” not to require a broader e-verify, as other GOP-led states have done, says Linden Melmed, former chief attorney for U.S. Citizenship and President Barack Obama, is the federal agency that oversees U.S. Citizens and Immigration Services and federal agencies. At least nine majority Republicans, including Arizona, Georgia, Florida and South Carolina, require most, if not all, private companies use the system. Abbott frequently places Texas as more immigrant-intensive than each.

Still, the private mission has made the session even more than ever before could explain the growing conflict between the pro-business side of the GOP in Texas and Republicans who want to see immigration more severe, said Melmed, former special adviser to Sen. John Cornyn of Texas.

Resistance against e-verify isn’t just Texan Republicans reluctant to regulate their businesses, Melmed said. It’s about how such a system will affect the state’s labor supply and economy.

More than 8% of the state’s workforce, an estimated 1.3 million Texas workers, according to a 2023 analysis of U.S. census data by the Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C., shows that about a quarter of all Texas construction workers lack legal status, and for example, the industry faces the necessary labor shortage of a housing boom. Similarly, the state’s understaffed agriculture, restaurants and senior care sectors are illegally dependent on workers here.

“If you take your application seriously [E-Verify]With a labor shortage, you’re going to create even worse problems,” said Bill Hammond, a former state legislator from GOP who once led the Texas Association.

Texas political leaders know this, Hammond said, but they don’t want to admit it publicly.

Abbott’s spokesman declined to say whether the governor supports mandating the program for private companies. But when he ran for governor more than a decade ago, Abbott admitted that he was complaining about the company setting up the system. At the time, he touted federal statistics that e-verify was 99.5% accurate. He said state agencies could serve as models before legislators impose it on businesses.

A spokesman for Lt. Col. Dan Patrick, who failed to push the law to hold employers accountable for illegally hiring immigrants here as a senator, did not reply to a request for comment, and a spokesman for Speaker Burrows did not explain why the house refused to e-procurement. Kolkhorst rejected repeated interview requests for her laws.

State Sen. Charles Schwartner, a Georgetown Republican who wrote the first e-verify bill approved by the Texas Legislature, said in an interview that his 2015 legislation would not be as good as he likes. He said he agreed to the task of Korkholt’s private business.

“We need to enforce immigration laws both at the borders and within Texas, and e-verify is a key factor,” Schwartner said.

Among the GOP lawmakers who pushed the session, faced “deafening silence” from many of their colleagues, said Rep. Carl Tepper, a R-Bock Republican, who introduced two e-Verify bills.

He said lawmakers and industry groups have “misplaced fears” about losing some of the workforce that is illegal here and that they feel they are dependent on. While immigration enforcement is being overseen by Congress, Tepper said the state should do what it can to prevent such workers from coming to Texas by making it more difficult for them to hire them.

Even one of the state’s most influential and conservative think tanks supports more progressive electronic verification laws, including expanding state mandates to local governments. Selene Rodriguez, campaign director at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, said doing so would be a “easy victory” than asking businesses to do so. Still, she said she was disappointed that the organization generally supports a broader mission and was disappointed that Kolhorst’s laws failed.

e-verify was tricky to her group, Rodriguez admitted. This is because lawmakers have done little for many years and have had to prioritize “attainable.”

“Given Trump’s agenda, he won so widely, so we thought there was a more desire to move it forward,” Rodriguez said. “But it wasn’t.”

She denounced “behind the scenes” lobbying, especially from strong industry groups in agriculture and construction, and denies lawmakers worried about how support for the proposal would affect the prospects of reelection.

Twelve prominent state industrial groups declined to comment on Propobrica and the Texas Tribune on their stances related to e-verify.

e-verify supporters acknowledge that the system is not a panacea. Computer programs can only check whether the identification document is valid, not whether the identification document actually belongs to a future employee. As a result, the black market for such documents has skyrocketed. Employers can also play the system by contracting work to small businesses that are exempt from e-verify duties in many states.

The American business community was a force of immigration reform. what happened?

Even when states adopt these, most lack strong enforcement. Texas legislators have never appointed agents to ensure that all employers comply. One of the toughest enforcements, South Carolina, has said Madeline Zavodney, a professor of economics at the University of North Florida who studied the program for the 2017 Dallas Bank Report, audits companies by randomly auditing whether they are using e-verify. But South Carolina has not confirmed whether businesses actually illegally hired immigrants here, says Alex Nowrast, vice president of economic and social policy studies at the Cato Institute, which is leaning towards libertarians in Washington, DC, that some states have carved out for small businesses or certain employers who often rely on unidentified labor. North Carolina, for example, exempts temporary seasonal workers.

The immigrants here have contributed billions to the economy, according to Tara Watson, an economist at the Brookings Facility, a think tank in Washington, D.C. Much of the rhetoric on this issue robs “they use immigration as a wedge issue to take away the fact that they are concerned about cultural change but at the same time they don’t want to disrupt the economy.”

He said expanding e-verify “is not actually a concern to anyone.”