This article was written in collaboration with the current article for ProPublica’s local reporting network. Sign up for Dispatch to get stories like this as soon as it’s published.

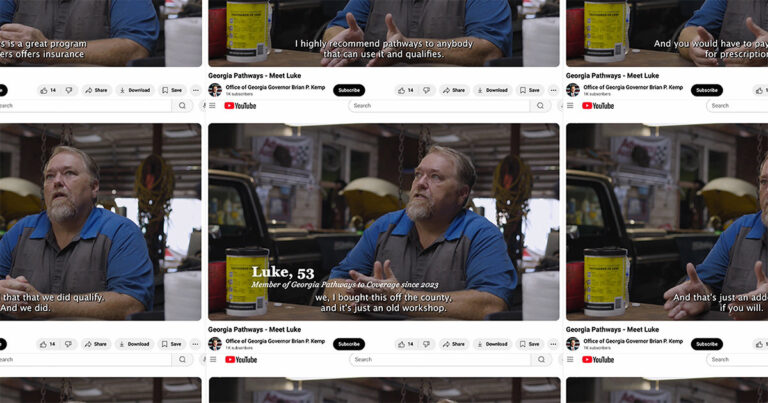

As political debates swirled over the future of Georgia’s Medicaid work requirements last summer, Gov. Brian Kemp held a press conference to release a three-minute testimony video featuring mechanics working in classic cars.

Luke Seaborn, 54, from the countryside of Jefferson, has become the de facto face of Georgia’s path for coverage, Kemp’s insurance program for poor Georgians. Seaborn explained how he improved his life in the year he was insured in a soft Southern draw. “Pathways is an incredible program that offers health insurance to low-income professionals like me.”

Kemp praises the pathway as an innovative way to reduce the high percentage of state uninsured adults while curbing government spending, and maintains the program as an example of other Republican-led states eager to enact Medicaid work requirements.

However, nine months after Seaborne’s video testimony was released, his opinions on the route plummeted. His profits have been cancelled – because of the bureaucratic deficit, he said.

“I thought the route was a blessing,” Seaborne recently told Current and Propobrica. “Now, that’s it.”

The Seaborn experience is not a symbol of lasting success, but shows why the program struggles to gain traction despite the state spending millions of dollars on the Pathways brand. Current and Propublica previously reported that many of the roughly 250,000 low-income adults eligible for the health insurance program may be struggling to register or maintain coverage.

Pathways politics wasn’t bothered Seaborn’s mind when Seaborn received a call from an insurance executive who handled Pathways clients. Seaborn, one of the first Georgians to sign up for the program in 2023, had written a letter thanking the insurance provider for covering the back pain procedure. The executives at Amerigroup Community Care wanted to know. Will he be taking part in the promotional video for Pathways?

Seaborn, a supporter of the governor, said yes without hesitation. Shortly afterwards, Kemp’s spokesman Garrison Douglas arrived at an auto repair shop several miles from the governor’s hometown, where he spent hours filming in a garage filled with vintage Ford and Chevrolet trucks and hand-drawn gas station signs.

A trained chemical engineer, Seaborne had quit his corporate job to embrace his dream of repairing a classic car. But the reality of being an owner of a small business made that path difficult, saying he would be in charge of the costs of health insurance, especially for himself and his son. The road softened the road, he said.

Seaborn said he was surprised when the governor called him by name at a press conference where the video of his testimony was released a few weeks later. He didn’t expect to be a singular face in the path.

By November, however, Seaborn had encountered some of the issues that other Georgians had exacerbated their opinions about the route. Seaborn said he recorded his working hours in the online system once a month when necessary. However, his interests were cancelled after he failed to complete the new form, which the state said had added without proper warning. Seaborn said it requested the same information the form had submitted monthly in a different format. The state’s Medicaid agency did not answer questions about Seaborne’s experience or new forms.

He said he called the same insurance executive who asked him to take part in the testimony. He recalled that she told him she would have lunch with one of Kemp’s aides that day and promised him to help. Within 24 hours, Seaborn said his benefits had recovered and representatives from the Georgia Family and Children’s Services Division were representatives administering the federal government’s benefits programmes that are called to apologise.

Douglas said the governor’s office was “not involved in the Seaborne case.” The insurance company did not respond to requests for comment.

Pathways subscribers must submit monthly documents proof that they have completed the required coverage requirements. However, the state says it does not verify monthly information only during registration and during annual renewals.

Seaborn said after his coverage was restored, his insurance company told him he would no longer have to file his working hours monthly. The next time he is required to submit such documents is during his annual re-registration. Nevertheless, Seaborn said it signed up for text and email notifications from the Pathways program to avoid being caught off guard if the requirements change again.

Still, technical glitches and more red tape left him losing coverage once more, he said. He stopped receiving text from the Pathways program in February. When I logged into the digital platform in early March and confirmed that everything was going well, the notification informed me that his benefits would end on April 1st. He said the surprise requirements have appeared on the digital platform, despite his reports not being updated.

“My head exploded,” he said. “I hadn’t received any texts or emails. I did what I was thinking, but that wasn’t enough.”

Seaborn said he went ahead and submitted the information, but that was delayed. He tried to call his insurance provider again for explanation – and helped. He also contacted the Family and Children’s Services department. However, this time he said no one called him.

In April, Seaborne paid out of pocket for him and his son’s prescription medication.

Ellen Brown, a spokesman for the Georgia Department of Family and Children Services, has not given the reason Seaborne benefits have ended.

The company running the struggling Medicaid experiment in Georgia has also been paid millions to sell it to the public.

“We are sorry to hear this happened, but we are looking at ways to serve our customers and resolve future communication gaps,” Brown said in writing Friday. “Every Georgian who wants our services is important and we take these issues very seriously.”

Meanwhile, Seaborne received a call that day from the same department of family and children’s services representatives who apologised to him after starting the route last fall. He said she said she would confirm he had regained his coverage. Representatives did not respond to requests for comment from current and Propublica.

On Monday evening, Seaborn received a text message to alert him to the notification on The Pathways Digital Platform. He logged on: Notification confirmed that he was re-registered. He is a change of fortune that he praised state officials for his plight as he had already given up on contacting people for help.

“I’m very frustrated with this whole trip,” Seaborn said. “I am grateful for the press. But what I don’t understand is that they leave me like mushrooms in the dark, giving me nothing, nothing information.”