Spain’s BBVA, as a legal entity, and some of its former senior executives are facing prosecution on a number of charges, but it still wants to take over its third biggest rival. The ECB has already given its blessing.

For the first time ever, Spain’s national government has launched a public consultation on a proposed corporate buyout, sparking accusations from market players of government interference and overreach. The buyout in question is the hostile takeover bid launched last May by BBVA, Spain’s second largest bank by assets, against Banco Sabadell, the smallest of Spain’s big four lenders, which would further consolidate Spain’s banking sector.

Melding the two lenders together would create a bank with more than 1 trillion euros in total assets, which may be enough to propel the newly bloated lender onto the Financial Stability Board’s leader board of Global Systemically Important Banks, or G-SIBs, some time in the near future. In other words, BBVA would become, like its biggest domestic rival, Grupo Santander, officially too big to fail.

However, it would also create a lender that, like Santander, is too big to bail. Needless to say, Spain’s Pedro Sánchez government is strongly opposed to the proposed merger. Economy Minister Carlos Cuerpo says the main goal of the consultation is to gather “useful” information on what the Spanish people think about BBVA’s “hostile” takeover bid before deciding what action to take.

“As in other public consultations regarding our regulatory framework, those citizens, organizations, associations and economic agents who may be affected by the operation can participate,” said Cuerpo.

Once the consultation is complete, at the end of this week, the Ministry of Economy will have a week to analyse the information provided before deciding whether or not to recommend that the Council of Ministers try to block the proposed buyout or impose draconian conditions on Sabadell the deal.

Wiretaps, Blackmail and Shake-Downs

What makes this takeover bid particularly controversial is that both BBVA, as a legal entity, and some of its senior executives, former and current, are facing criminal prosecution over charges of widespread corporate spying and disclosure of rival companies’ secrets. The eight former executives facing charges include BBVA’s long-time president, Francisco González (2000-2018), and its former CEO, Ángel Cano.

For a period of 12 years (2004-16), BBVA hired the services of Grupo Cenyt, a private investigation firm belonging to former police chief Jose Manuel Villarejo, to spy on businessmen, politicians and journalists on behalf of the bank. Villerejo is currently serving a 19-year prison sentence for using Grupo Cenyt to wiretap, blackmail, and threaten people at the request of companies and private individuals, including, it seems, BBVA.

While other Spanish corporations, including Repsol, Iberdrola and CaixaBank, also hired Villarejo’s services, it was BBVA that would go on to become his biggest client, paying more than $10 million in fees and commissions.

In 2004, BBVA hired Cenyt to investigate executives at the construction company Sacyr, which was looking to buy a stake in the bank, as well as government officials in the former administration of Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero. The bank’s then-president, González, allegedly instructed his security chief to hire Villarejo to wiretap the phones of Sacyr’s president, the Spanish prime minister and the head of the administration’s economic office.

In the years that followed, Villajero is alleged to have spied on and, in some cases, bribed, intimidated and/or spread fake news, on a host of prominent figures, including senior executives of some of the bank’s largest rivals and corporate debtors, financial regulators, journalists, government ministers, members of the left-of-centre political party, Podemos, and the then-King of Spain Juan Carlos. In total, Cenyt’s team of private investigators listened to 15,000 phone calls on behalf of the bank.

Villarejo has been in prison since 2017, where he could one day be joined by the current and former BBVA executives accused of hiring his services if they are found guilty of the charges they face — I know, senior bankers don’t go to jail in this post-Lehman world, but one can still dream, can’t one?

As reader vao put it in a comment to a previous post, the reasoning why banks or bankers should be treated as “too big to jail” is that “even if the problems [facing a struggling or bankrupt bank] were caused by illegal shenanigans, members of its management are too influential and bringing them to account would ruin the confidence amongst economic actors.”

For the moment, BBVA’s lawyers are working around the clock to try to stall the trial, particularly as it tries to take over its third largest rival in an operation that nobody but itself and the ECB seems to want. So far, all its trial appeals have been struck down. The bank has also been accused of not cooperating with Spain’s National Court over requests for emails and other documents as well as refusing to share information on the case with its own shareholders — you know, the sort of things that only the biggest banks tend to get away with.

Banco Sabadell’s President, Josep Oliu, has underscored the risks of Sabadell being bought out by a rival bank that is currently in the dock (or at least should be):

The bank is facing criminal prosecution. If the result of these accusations is that it is found guilty, it could have a major impact on the value of its stock. Sabadell’s shareholders should know this. Transparency is needed.

A Heavily Concentrated Sector

But BBVA’s legal pickle is seemingly not serious enough a matter to prevent Spain’s main market regulator, the National Commission on Markets and Competition (CNMC), from approving its proposed hostile takeover bid. However, the regulator did require certain binding commitments from BBVA, such as keeping bank branches open in areas with fewer competitors and maintaining the lending conditions Sabadell has already provided to its SME clients.

The Spanish government insists, however, that there are compelling competition and prudential reasons for blocking the proposed merger. Spain’s banking industry, it says, is already concentrated enough, with the four biggest lenders — Banco Santander, BBVA, CaixaBank, and Sabadell — controlling over 70% of the retail banking space. Before the 2008 financial crisis, the country was home to 45 savings banks and a dozen commercial banks. Now there are barely ten large and mid-size lenders left.

The consultation is not a referendum, and therefore its result is not binding. However, according to sources cited by El Diario, the government is trying to arm itself with as many arguments as possible to hamper BBVA’s hostile takeover bid. As we have previously reported, another merger in Spain would have a clear negative impact on banking competition and stability. However, the European Central Bank does not see this as a problem — in fact, it is proactively encouraging greater bank concentration in the Euro Area:

BBVA’s proposed takeover of Sabadell… faces strong opposition from the national government in Madrid, but it has received the blessing of the European Central Bank, which has long favoured thinning the herd of banking players in the Euro Area.

As the German economist and small bank activist Richard Werner warns, economies with fewer and bigger banks will lend less and less to small firms, which tends to mean that productive credit creation that produces jobs, prosperity and no inflation, also declines, and credit creation for asset purchases, causing asset bubbles, or credit creation for consumption, causing inflation, become more dominant.”

In other words, more financialisation, less productive activity. In the eurozone, more than 5,000 banks have already disappeared since the ECB started business a little over two decades ago, according to Werner. And the central bank is determined to continue, if not intensify, this process…

A BBVA-Sabadell tie up would not only further erode competition in an already heavily concentrated financial sector, with all the ugly implications that entails (including more cartel-like behaviour, higher risks of big bank implosions, and the inevitable closure of even more bank branches and ATMs, making accessing cash even harder, just as the big banks intend), it is also likely to impact the banking services available to small businesses… Sabadell is Spain’s largest lender to small and medium-size enterprises.

Catalonia’s association for SMEs, Pimec, has warned that a further concentration of the banking sector of this magnitude could lead to a reduction in the credit available to SMEs of up to 8%.

“This is equivalent to more than €54 billion that could stop reaching business projects, innovation initiatives and new employment opportunities,” says Oriol Amat, president of the SME Observatory of Catalonia:

In other words: less capacity to grow, less room to face new challenges and more difficulties in maintaining an economic model rooted in the territory.

In this case, we are not dealing with the rescue of banks in difficulty, as happened after the 2008 crisis. On the contrary, the takeover bid takes place between two profitable and solvent entities. Precisely for this reason, it is more difficult to justify it from a point of view of general interest. There is no clear economic urgency that explains it, but a desire to increase market share and profitability on the part of the offering entity. And when the market is concentrated, the plurality, proximity and negotiation capacity of many agents, especially SMEs and local businesses, are often reduced.

Many of Sabadell’s (largely Catalan) retail shareholders, who hold just under half of the bank’s stock, are against the proposed merger. In an effort to frustrate BBVA’s designs, Sabadell refused to disclose not only the non-public information that BBVA has requested to draft the prospectus of the hostile takeover but also data that it has willingly disclosed for years, including the proportion of shares held by individual and institutional shareholders.

In its latest attempt to derail BBVA’s hostile takeover bid, Banco Sabadell has even proposed launching a merger of its own, with a smaller banks such as Abanca or Unicaja, with which it would arguably have a much better fit than with BBVA. Perhaps most important of all, they have very different geographic markets: Sabadell is particularly strong in Spain’s Mediterranean coastal region, Abanca’s operations are primarily in the north-western region of Galicia and Unicaja’s primary market is Andalucia.

It is too early to tell whether such a plan will prosper, but the fact that Sabadell is desperately trying to avoid BBVA’s hostile takeover by trying to negotiate a last-minute merger of its own speaks volumes of the stakes involved.

“We are talking about excessive concentration within this sector and this has potential effects for customers, for example, in how their deposits are remunerated,” said Carlos Cuerpo, Spain Minister of Economy. The minister recalled that over the past two years the ECB’s sharp rise in interest rates has not led to a commensurate rise in deposit rates, as it did on previous occasions:

“The Bank of Spain itself points out that, in part, this is due to a possible absence of competition or excessive concentration, and this is before an additional merger between two of the large Spanish banks takes place.”

Spain is not the only EU Member State whose government is trying to block a hostile takeover bid. In September, the then-German Chancellor Olaf Scholz described Italian too-big-to-fail lender Unicredit’s underhand attempts to take over Commerzbank, Germany’s second largest lender, by buying up shares in the German sold by the Scholz government itself, and lambasted what he called efforts “to aggressively acquire stakes in companies without any cooperation, without any consultation, without any feedback.”

If UniCredit were to take control of Commerzbank and merge it with its current German subsidiary HypoVereinsbank, it would create the largest bank in Germany and one of the largest in Europe. But if faces strong opposition, not only from government but also from elements of Germany’s business sector.

Like Sabadell, Commerzbank is a key lender to Germany’s small and medium-sized businesses — the so-called Mittelstand. There is a fear that if control over the bank was passed to a bank in another country, the parent bank might cause a credit squeeze in Germany if it ran into difficulties at home. And let’s face it: Italian banks, including Unicredit, are not exactly known for their stability.

This hostility towards bank mergers, often driven by fears of losing national champions to foreign rivals, is pitting some national governments against the European Central Bank and EU Commission, which are determined to help create European banking champions capable of competing with US and Chinese mega-lenders.

Senior ECB representatives have persistently sought to reduce the number of small and mid-sized banks in the Euro Area. In September 2017, Daniele Nouy, the then-Chair of the ECB’s Supervisory Board, partly blamed the low profitability of large lenders on the fierce competition from smaller banks. Rather than lots of competition between domestic banks, what Europe needs, Nouy said, are “brave banks” willing to traverse borders and conquer new territory.

In September last year, the ECB gave the green light to BBVA’s acquisition of Sabadell. Then in March this year, it granted approval for Unicredit to increase its stake in Commerzbank to just under 30%, marking a significant step towards a potential takeover of the German banking institution. A few weeks ago, ECB Supervisor Claudia Buch urged Europe to harmonise bank merger rules, in order to facilitate cross-border mergers.

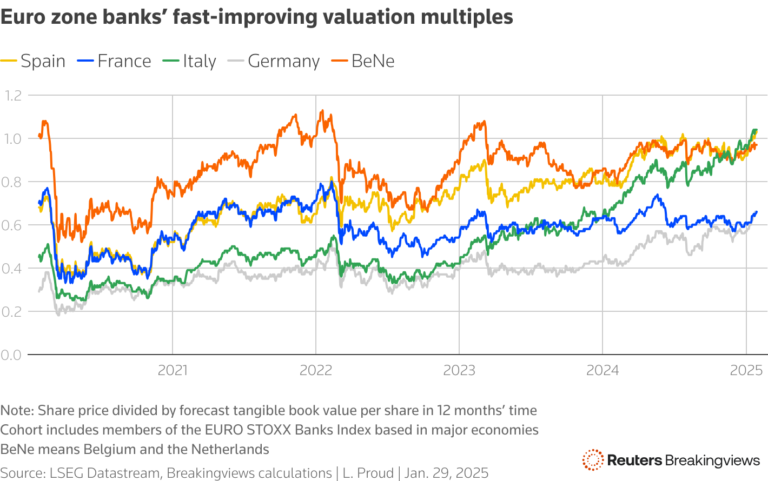

However, most of the large bank mergers currently in the works are of a hostile nature. They include BBVA’s attempted takeover of Sabadell as well as Unicredit’s moves on Commerzbank and its Italian rival, BPM, which would create Italy’s largest bank by assets. As a recent Reuters Breaking Views report points out, the main reason why hostile takeovers are back on the menu in Europe is the sudden emergence of two basic conditions: first, determined bidders like Unicredit and BBVA, and second, a target board with the confidence to say no:

Both became present, rather suddenly, in recent years for European banks.

Rising interest rates boosted returns on equity, valuation multiples and animal spirits across the sector. By 2024, would-be acquirers found themselves with excess equity capital and a relatively rich acquisition currency for the first time in many years. Since share buybacks make less sense with higher valuations, M&A rose to the top of the agenda.

Yet the same forces also made perennial underperformers – like Sabadell, BPM and Commerzbank – more viable standalone players, empowering their boards to reject takeover interest. If Orcel and Torres had laid down formal bids a few years ago, when smaller lenders’ share prices and returns were much lower, it’s harder to imagine much of a fightback.

In mid-2022, for example, just a quarter of the current members of the EURO STOXX Banks Index had a consensus 12-month-forward return on tangible equity estimate that exceeded 10% – a typical rule of thumb for the sector’s cost of equity. Now, 85% of the same group are on track to exceed that key profitability threshold, according to Breakingviews calculations using analyst forecasts gathered by LSEG.

In other words, the very factors that encouraged the acquirers also gave the targets reasons to resist, making unwelcome or downright hostile approaches the only viable option. Orcel, for example, didn’t bother to negotiate with BPM’s board before bidding in November because of the likely intransigence, a person familiar with the matter told Breakingviews. Possible future aggressors, like 51-billion-euro Dutch bank ING (INGA.AS), opens new tab or 75-billion-euro Italian giant Intesa Sanpaolo (ISP.MI), opens new tab, might find themselves in a similar situation.

However, as Reuters notes, most hostile bank takeovers in Europe have not prospered — according to LSEG’s M&A database, of 24 hostile and unsolicited $1 billion-plus deals attempted by European banks, only five closed, for a 21% completion rate — while those that do often tend to end in disaster. The most notorious example is the 2007 Royal Bank of Scotland-led 71-billion-euro carve-up of Dutch group ABN Amro, which resulted in bailouts for several members of the acquiring consortium.

This episode of relatively recent history should (but unfortunately probably won’t) serve as a cautionary tale for the banks and central banks looking to usher in a new age of mega-mergers.