When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the Confederates, like governments of all circumstances, had three sources of money: taxation, borrowing, or printing.

Taxation

Confedycy stabbed Throupot to withdraw taxes from the citizens. “The Congress enacted a small tariff in 1861,” writes Historyn James M. McPherson. “In August 1861,” I continued:

…A direct tax on actual personal property and individual property has become law. The Richmond government relied on the state to collect this collection. Only South Carolina did that. Texas confiscated property owned by northern ownership and paid the assessment. All other states paid their allocations by borrowing money or printing them in the form of state notes, rather than collecting taxes!

In April 1863, more financial comprehensive measures were enacted, including the collection of 8% for certain good measures held for Salet, Excel and licensing obligations, and the 10% profit tax intended to punish “speculators.” However, because the Confederates needed actual resources rather than depreciation papers, they were allowed to “tax” on agricultural products, alienating a large strip of population. Many were willing to die for Confedeay, few were willing to pay for it.

Borrowing

Confedy’s ability to borrow predicted a victory prospect. “The first $15 million bond issue was subsidized immediately,” writes McPherson.

Subsequent lawsuits by Congress in May and August 1861 approved the issuance of $100 million in bonds with 8% interest. The boys sold slowly. Even southerners who had spare cash had invested in dipad in patriot preparation of BU bonds at 8%, when inflation rates had already reached 12% per month by the end of 1861.

Moreover, both taxation and borrowing aimed at withdrawing cash from the Relativley Cash Poor Society. Most of the Confederate capitals were bound by non-liquid forms of land and slavery. “Confederate states owned 30% of the state (in the form of real and personal property), but only 12% of the circular currency and 21% of the bank’s assets,” he wrote.

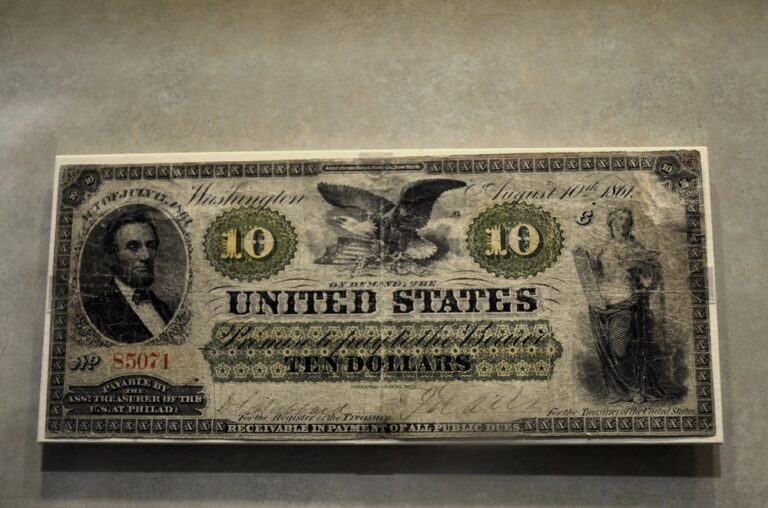

printing

Therefore, Treasury Secretary Christopher warns that Confedeay had few options to print it out as “the most dangerous of all ways to collect money.” Congress granted $20 million to be issued by the Treasury in May 1861, $100 million in August, $50 million in December, and another $50 million in April 1862.

…The Confederate government has earned three-quarters of its revival from the press, nearly a quarter of its bonds (some purchased with the same Treasury bonds), and less than 2% from taxes. In later years there was a slight belief in loan and tax experts, but Confedeay was funded primarily with $1 billion and half of the paper…

Memming warned that “the massive amounts of money in circulation today must cause depreciation and fiscal disasters.” “The currency gradually declined at first, as the Confederate victory in the summer of 1861 was strengthened,” writes McPherson. Economist Eugene M. Lerner said that in June 1862 the real value of money stock was 2% higher than January 1861, so that money stock increased faster than product prices. Prices then rose more rapidly than money stock, and their true value fell. By January 1864 it was 58% lower than January 1861, and at the beginning of 1865 it was less than about 80%.

As military set-offs darkened Confederate properties, Confederate memo holders began to doubt their promise to redeem them at face value within two years of the end of the war, and began offloading as soon as possible. “She asked me $20 for a five-dollar egg, and she said she would take it to the ‘Confederate’,” wrote Dearist Mary Chestnut in 1864.

From the perspective of the exchange equation, the demand for holding money balances collapsed, speed (v) rose sharply, strengthening the inflationary pressure (M) and decline in production (Y) of an increase in money supply (M). Milton Friedman famously claimed:

Inflation is always up to financial phenomena in the sense that it is produced only by increasing the amount of money more rapidly than output.

This excludes the role of money demand. Elsewhere, Friedman summed up too much inflation (P) (M) chasing (V) too few products (Y). This fits well with the Confederate hyperinflation story.