Valerie A. Lamie of the Hoover facility has a new NBER paper examining the impact of lump sum transfer payments on AGGGAGATE demand. Here’s the summary:

This paper uses evidence from four case studies to reassess the effectiveness of temporary transfers in stimulating macroeconomics. Revitalization of Keynes’ stabilization policy is important for the benefits of these polyedes, as it has prolonged costs with regard to higher debt passes. Each case study analyzes whether the behavior of aggregated data is configured with transfers that provide effective stimuli. Two of the case studies are reviews of evidence from my recent research on US taxes in 2001 and 2008. The other two case studies are new analysis of temporary transfers in Singapore and Australia. In all four cases, evidence suggests that temporary cash was not transferred to households or provided little or no stimulus to the macroeconomics.

This comment my eyes:

No evidence is found that Singapore’s election year payments will stimulate the macroeconomics. These results are the consumption of tax rebates in the United States for 2001 and 2008, as summarized in the previous section. But we have a puzzle left. Why does the high household MPC estimated by Agarwal and Qian (2014) not appear in total consumption? Because microdata is currently inaccessible, future research will leave it possible to coordinate the outcomes of competing micro and macros.

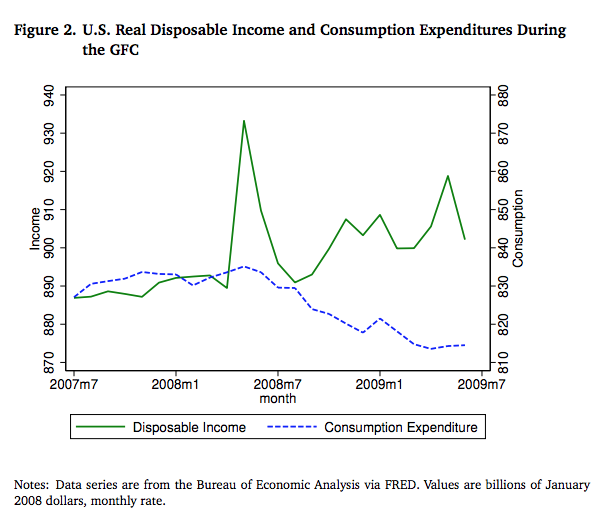

Let’s take a look at examples of 2008 tax rebates that occurred in April and May. For discussion, assume that 75% of households were prescribed with a $1,000 check, while the other 25% did not collect the rebate. Also, assume that the rebates will lead households who will chair to increase spending by 4% while others are not unfair. In that case, rebates may have been treated to increase consumption by 3% in total.

However, during this period, inflation was accelerating rapidly, mainly due to rising commodity prices and significantly weaker. The Fed has been a result of responding to this inflation and tightening its monetary policy. This did not take the form of an increase in interference rates despite a sharp drop in natural interest rates in mid-2008. Assume that the Fed’s strict money policy has now tended to reduce spending by 3% by all households.

Combining fiscal stimulus efforts with tough money, you may be expected to consume 3% less than before, which could be your main side household. In that case, monetary policy completely offset the broadening effect of fiscal stimulus.

Of course, this example is merely an example of financial offsetting. Nevertheless, even if macro data is ineffective, it suggests that “microdata” (i.e., home behavior) may suggest that fiscal stimulus measures work. When financial policymakers are at work, they should always completely offset the prosecutor’s policy initiatives, which consist of lump sum taxes and transfer changes. (Changes in marginal tax rates may have an effect on supply.)

Ramey’s paper provides numerous graphs showing what Pro change and consumption are. Note how tax rebates have soared the May 2008 Prokebubble spike.