ProPublica is a nonprofit news company that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive the biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

Lifesaving HIV treatment. Treatment for hepatitis C. New tuberculosis treatments and RSV vaccine.

These and other major medical advances exist largely thanks to a major division of the National Institutes of Health, the largest funder of biomedical research on the planet.

For decades, researchers funded by the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases have quietly worked in red and blue states across the country, conducting experiments, developing treatments, and Clinical trials have been conducted. With a budget of $6.5 billion, NIAID keeps the nation at the forefront of infectious disease research and has played a critical role in discoveries that save millions of lives.

Then the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic occurred.

NIAID helped lead the federal response, and its director, Dr. Anthony Fauci, sparked a firestorm amid nationwide school closures and mask-wearing recommendations. Lawmakers were outraged to learn that authorities had funded a Chinese lab that was engaged in controversial bioengineered virus research, and questioned whether there was sufficient oversight. Congressional Republicans have led numerous hearings and investigations into NIAID’s activities, flattened the NIH budget, and proposed an overhaul of the agency.

Recently, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., whom President Trump nominated to head the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees the NIH, fired and replaced 600 of the agency’s 20,000 employees and shifted research to infectious diseases. He said he would like to shift away from vaccines and vaccines. These are core to NIAID’s mission to understand, treat, and prevent infectious, immunological, and allergic diseases. He said half of the NIH budget should focus on “preventive, alternative, and holistic approaches to health.” He has a particular interest in improving eating habits.

Even the NIH’s staunchest defenders agree that the agency could benefit from reform. Some want to reduce the number of institutes, while others think there should be term limits for directors. There are significant debates over whether to fund it, how to oversee controversial research methods, and concerns about how authorities will respond to transparency. Scientists inside and outside the institute agree that they need to work to restore public trust in the institute.

But experts and patient advocates say overhauling or dismantling NIAID without a clear understanding of the important work being done at NIAID will not only affect the development of future life-saving treatments but They worry that it could also jeopardize the country’s position as a leader in biomedical innovation.

Good journalism makes a difference.

Our nonprofit, independent newsroom has one job: to hold those in power accountable. Here’s how our research is driving real-world change.

We are trying something new. Was it helpful?

“The importance of NIAID cannot be overstated,” said Greg Millett, vice president and director of public policy at amfAR, a nonprofit organization dedicated to AIDS research and advocacy. “The amount of expertise, research and breakthroughs that have come out of NIAID is simply incredible.”

To understand how NIAID works and what’s at stake with the new administration, ProPublica spoke with people who have worked for NIAID, those who receive funding from NIAID, I spoke with people who have served on boards and panels that advise NIAID.

decision, decision

The director of NIAID is appointed by the NIH director and must be confirmed by the Senate. Directors have wide discretion to decide what research to fund and where to award grants, but traditionally those decisions are based on recommendations from external expert panels. I have been suffering.

Fauci led NIAID for nearly 40 years. He has weathered controversy before, particularly in the early days of the HIV epidemic, when local activists criticized him for initially excluding him from the research agenda. But until the pandemic, he generally had relatively solid bipartisan support for his work, including his focus on vaccine research and development. When he retires in 2022, he will be replaced by Dr. Jeanne Marazzo, an HIV researcher and former head of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. She has spent much of her time on the floor of Congress working to restore bipartisan support for the agency.

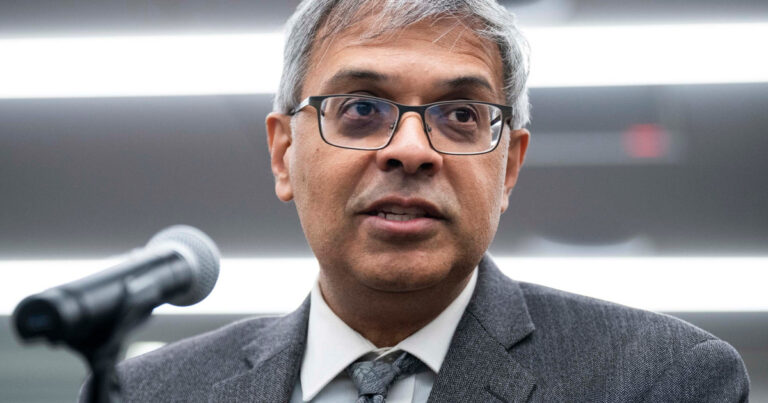

NIH directors typically span multiple presidential administrations. But Donald Trump nominated Dr. Jay Bhattacharyya to lead the NIH, and current director Dr. Monica Bertagnoli told staff this week that she would resign on January 17th. Bhattacharyya, a professor at Stanford University, has spent his career researching health policy issues such as health policy implementation. The effectiveness of the Affordable Care Act and U.S. funding for international HIV treatment. He also researched the NIH and concluded that while it funds a lot of innovative or novel research, it should be doing more.

In March 2020, Bhattacharya co-authored an opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal saying that the death toll from the pandemic was likely far lower than predicted and calling for a reassessment of lockdown policies. In October of the same year, he helped author a declaration recommending lifting COVID-19 restrictions for people with “minimal risk of death” until herd immunity is achieved. In an interview with the libertarian magazine Reason in June, he said he believed the coronavirus outbreak most likely stemmed from a laboratory accident in China, which led to the development and distribution of the new coronavirus. He said he did not understand President Trump’s Operation Warp Speed. – 19 vaccines administered with unprecedented speed and complete success as they were all part of the same research project.

Mr. Bhattacharya declined ProPublica’s request for an interview about his priorities. A recent Wall Street Journal article in which he said he was considering ways to link “academic freedom” on college campuses to NIH grants, but how he evaluates that and how It is unclear whether such changes will be implemented. He also raised the idea of term limits for directors, saying the pandemic was “just a disaster for science policy and public health policy in the United States” and that reform is now desperately needed.

where the money goes

Grants from NIAID flow to nearly every state and more than half of the nation’s congressional districts, supporting thousands of jobs across the country. Last year, nearly $5 billion of NIAID’s $6.5 billion budget went to U.S. organizations other than its institutes, according to a ProPublica analysis of NIH’s RePORT, an online database of NIH spending.

In 2024, Duke University in North Carolina and the University of Washington in Missouri will be the largest recipients of NIAID grants, with more than $190 million and $173 million, respectively, for research into HIV, West Nile vaccines, and biodefense, among others. Received.

Over the past five years, $10.6 billion, or about 40% of NIAID’s budget to U.S. external agencies, went to states that voted for Trump in the 2024 presidential election, the analysis found. Research shows that every dollar spent by the NIH generates between $2.50 and $8 in economic activity.

That money is key to advancing your career in science as well as medicine. Most students and postdoctoral researchers rely on the funding and prestige of NIH grants to enter this profession.

New drugs and global impact

The NIH pays for most of the world’s basic research on new drugs. The private sector depends on this public funding. Researchers at Bentley University found that NIH funding was behind every new drug approved from 2010 to 2019.

This includes treatments for children infected with respiratory syncytial virus, a COVID-19 vaccine, and a treatment for Ebola, all with significant patents based on NIAID-funded research. There is.

NIAID research has also improved the treatment of chronic diseases. New understanding of inflammation from NIAID-funded research has led to cutting-edge research into treatments for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and has led to the spread of viruses ranging from multiple sclerosis to the long-lasting coronavirus. A growing body of evidence shows how it can have long-term effects. When private companies turn their research into blockbuster drugs, the public benefits not only from jobs and economic growth, but also from new treatments.

The weight of NIAID’s funding also allows it to play a less prominent role that has been essential to scientific progress and the U.S. role in biomedicine, according to people familiar with the matter.

The institute brings together scientists, usually competitors, to share discoveries and tackle big research challenges. Matthew Rose of the Human Rights Campaign, a member of multiple NIH advisory committees, said having a neutral space is essential to advancing knowledge and ultimately spurring breakthroughs. He said that. “Academic societies are very competitive with each other. NIH bringing grantees together will help them talk to each other and share their research.”

NIAID also funds international researchers and ensures that the United States continues to have influence in the global conversation on biosecurity.

President Trump nominates Federal Housing Administration head, opposes efforts to help poor people

NIH is also working to improve representation in clinical trials. Clinical research continues to be dominated by heterosexual white men, which means women, all people of color, and even members of the LGBTQ+ community are being overlooked. Rose pointed to the long history of overlooked signs of heart disease in women as an example. “These are the kinds of things that commercial companies aren’t interested in,” he said, noting that the NIH helps set the agenda on these issues.

Nancy Sullivan, a former senior scientist at NIAID, said the power of NIAID is its ability to invest in a broader understanding of human health. “Basic research is what makes it possible to develop treatments,” she says. “You never know which piece of basic research is going to be central to treating a disease, defining a disease, and knowing how to treat it,” she says.

Ms. Sullivan should know: It was her work at NIAID that got the first Ebola treatment approved four years ago.