ProPublica is a nonprofit news company that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive the biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

Register for the virtual discussion on November 21st. In this discussion, reporters will guide you through ProPublica’s reproductive health coverage.

Georgia authorities have dismissed all members of the state commission charged with investigating maternal deaths. The move came in response to ProPublica obtaining an internal report detailing the two deaths.

In September, ProPublica reported on the deaths of Amber Thurman and Candy Miller, which the state Maternal Mortality Review Board determined were preventable. These are the first reported cases of women dying without access to care limited by the state’s anti-abortion laws, sparking outrage over the deadly consequences of such laws. The women’s stories became central to presidential campaigns and ballot initiatives on abortion access in 10 states.

“Confidential information provided to the Maternal Mortality Review Board was inappropriately shared with outside individuals,” state Surgeon General Dr. Kathleen Toomey wrote in a Nov. 8 letter to committee members. stated in a letter. “Although this disclosure was investigated, the investigation was unable to determine which individuals disclosed the confidential information.

“Therefore, the current MMRC will be dissolved with immediate effect and all member seats will be filled through a new application process.”

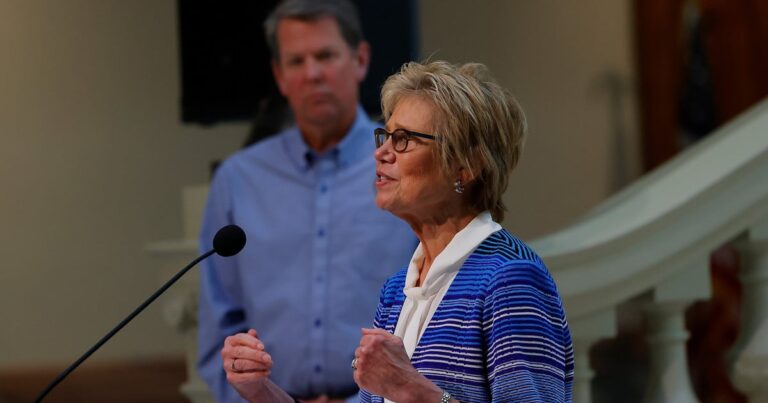

A spokesperson for the Department of Health declined to comment on the decision to fire the committee, saying the letter the department provided to ProPublica “speaks completely.” Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp’s office also declined comment, referring questions to the health department.

Under Georgia law, the Maternal Mortality Review Commission’s activities are confidential and its members must sign non-disclosure agreements. These members only see summaries of medical records with personal information removed, and findings about individual cases should not be shared with the public, even with the hospital or the deceased woman’s family. Shouldn’t.

The Ministry of Health’s letter states that new measures may be taken to hide the board’s deliberations from public view. The letter said the agency may change “the confidentiality, committee oversight, and other procedures for new committees to better ensure the organizational structure of the MMRC.”

Maternal mortality review committees exist in every state. They are tasked with investigating deaths of women during pregnancy or up to a year after pregnancy and determining whether those deaths could have been prevented.

Georgia has 32 permanent commissioners with diverse backgrounds, including obstetricians and gynecologists, cardiologists, mental health care providers, medical examiners, health policy experts, and community advocates. These are volunteer positions that pay a small honorarium.

Their job is to collect data and make recommendations, published in reports, aimed at combating systemic problems that could help reduce the number of deaths. The Georgia state commission’s latest report found that of 113 pregnancy-related deaths from 2018 to 2020, 101 had at least some possibility of prevention. Its recommendations led to changes in hospital care to improve the response to intrapartum emergencies and new programs to increase access to psychiatric treatment.

“Changes to the current committee will not delay the MMRC’s responsibilities,” the Ministry of Health’s letter states. But at least one other state has experienced delays as a result of commission restructuring. Idaho will allow its Maternal Mortality Review Commission bill to expire in July 2023, effectively eliminating the commission after a lobbyist group attacked the commissioner for recommending that the state expand Medicaid to postpartum women. Disbanded. The Idaho Legislature re-established the commission earlier this year, but new members were not announced until Nov. 15. There is currently a delay of more than a year in the review process.

Reproductive rights advocates say Georgia’s decision to dismiss and reorganize the commission could have a chilling effect on the commission’s work, making it difficult for commission members to discuss politically sensitive issues. It said it could discourage people from delving so deeply into the circumstances of a pregnant woman’s death in some cases.

“They did what they were supposed to do, and that’s why we need them,” said Monica Simpson, executive director of SisterSong, one of the groups challenging Georgia’s abortion ban in court. said. “With this sudden breakup, what I’m concerned about is what we’re going to lose in terms of time and data in the process.”

One of the aims of the Maternal Deaths Investigation Committee is to take a comprehensive look at the circumstances of the deaths and identify the root causes that can help other women in the future.

In Candy Miller’s case, the most striking detail in the state medical examiner’s report on her death was that she had a lethal dose of painkillers, including fentanyl, in her system. The cause of death was given as drug poisoning.

However, the Georgia State Commission considered the facts of the death for another purpose: to consider the broader context. A summary of Miller’s case prepared for the committee, drawn from hospital records and the coroner’s report, said Miller had multiple health conditions that could be exacerbated by pregnancy. , including ordering abortion pills from overseas and the presence of fetal tissue that had not been expelled. It indicated that the abortion was not completely completed. The family also told the coroner that she did not seek medical attention “due to current laws regarding pregnancy and abortion.”

The commission found her death was “preventable” and blamed the state’s abortion ban.

“The fact that she felt like she had to make these decisions, that she didn’t have good options here in Georgia, we felt that definitely influenced her case. ” one committee member told ProPublica in September. “She absolutely lives up to the bill.”

For Miller’s family, the commission’s findings were painful but desired. “That seems like important information to share with the family,” said Miller’s sister, Turiya Tomlin Randall. She didn’t know about the committee’s work until she was contacted by ProPublica.

She also said it was upsetting to hear that committee members were removed in part because her sister’s case was made public. “I don’t understand how that is possible,” she said.

The committee also investigated the case of Amber Thurman, who died just a month after Georgia’s six-week abortion law went into effect. The medical examiner’s report states that Thurman died of “sepsis” and “residual products of conception” and underwent a home abortion, dilation and curettage, or D&C, and hysterectomy.

When committee members received a summary of her hospital stay, they saw a timeline that included an additional element: The hospital required a D&C, which Thurman needed due to a rare complication. A routine procedure to remove tissue) had been delayed by 20 hours. The disease developed after taking abortion pills. The state recently imposed criminal penalties for performing D&Cs, with some exceptions. Doctors discussed twice about providing a D&C, but by the time they performed the procedure, it was too late, the summary said. Committee members determined there was a “good chance” that Thurman’s death could have been prevented if she had received the Doctrine and Covenant sooner.

The doctors and nurses who treated Thurman did not respond to ProPublica’s questions about the September article. The hospital did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Thurman’s family also told ProPublica they wanted information about her death made public.

Some experts say that confidentiality of the Maternal Mortality Commission’s report is important to fulfilling the commission’s objectives. Rather than assigning blame, it was established to provide a forum for clinicians to explore the broader causes of maternal health problems. But some say the lack of transparency could help obscure the biggest maternal health care mess in half a century.

“The report that came out of that committee was anonymized to provide a 50,000-foot view,” said Kwajalein Jackson, executive director of the Feminist Women’s Health Center, which provides abortion care in Atlanta. I am aware that it is a synthetic product.” “But what I’m concerned about is that in an effort to protect our nation, there’s so little information available to people who can change their behavior, change their procedures, change their strategies, change their behavior to change motherhood. Health outcomes.”

Texas lawmaker seeks new exception to state’s strict abortion ban after two women’s deaths

Two states actually changed their committee structure. In Idaho, the commissioner recommended expanding Medicaid but Republicans opposed it, and in Texas, the commissioner publicly criticized the state.

In 2022, Nakeenya Wilson, a Texas commission member and community advocate, opposed the state’s decision to delay releasing the report into an election year. The following year, Congress passed legislation creating a second community advocate position on the commission, redefining the position, and forcing Wilson to reapply. She was not reappointed. Instead, the state filled one of the slots with a prominent anti-abortion activist.

Wilson said Georgia’s decision to fire the commission could cause more damage.

“What message does it send to families who have lost a loved one?” she said. “There will be even less responsibility to ensure that something like this never happens again.”

Ziva Branstetter, Kavitha Surana, Cassandra Jaramillo and Anna Barry-Jester contributed reporting. Doris Burke contributed to the research.