ProPublica is a nonprofit news company that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter focused on fraud across the country, and get it delivered to your inbox every week.

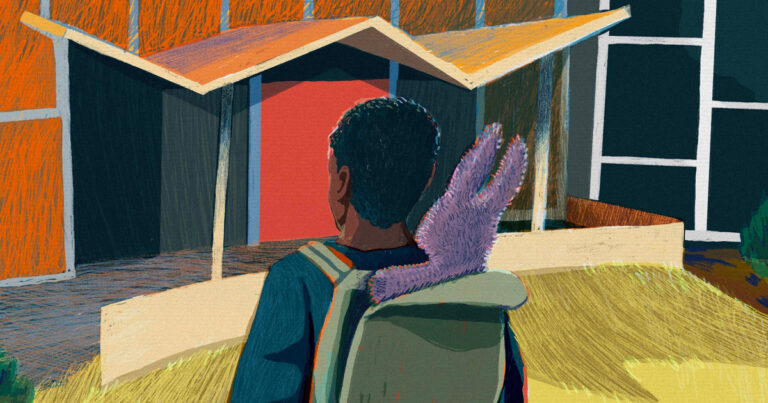

On the second day of school this year in Hamilton County, Tennessee, Ty picked out a purple bunny from among the hundreds of stuffed animals in his room. While his mother wasn’t looking, the 13-year-old boy slipped it into his backpack and showed it to his friends.

The day marks the 10th anniversary of his favorite video game series, Five Nights at Freddy’s, of which Bonnie the bunny is one of the stars. Ty has autism and Bonnie is his greatest comfort when he feels upset or discouraged. No one other than Ty is allowed to touch Bonnie, not even his mother.

Ty first attended Ooltewah Middle School, just east of Chattanooga. According to Ty and his mother, in class that morning, Ty told his teacher that he didn’t want anyone to see inside his backpack because he was worried that his toys would be confiscated. When the teacher asked why, Ty said, “Because the whole school is going to explode,” he and his mother recalled.

Ty’s mother said school officials acted quickly. The teacher, who had known Tai only for a day, called school administrators, and police intervened. They take Ty to the counselor’s office and find Bonnie in his backpack. As Tye stood there, confused as to what he had done wrong, police handcuffed him, patted him down and put him in the back seat of a squad car, he said. .

“I think they thought I had a real bomb in my backpack,” Tai told ProPublica and WPLN. But he didn’t have a bomb. “Right here,” he said, holding Bonnie. “And yet they took me to prison.”

The Sheriff’s Office issued a press release about the incident, saying that when police inspected the backpack, “it was found that it did not contain any explosives.” ProPublica and WPLN are using a nickname at the request of Ty’s mother to protect her identity because she is a minor. The sheriff’s office did not respond to questions about Tai’s case. The Hamilton County School District, which includes Ty’s school, refused to respond, even though his mother signed paperwork giving permission to authorities.

Highlights of this series

Ty’s arrest is the result of a new state law that requires those who make threats of gang violence at schools to be charged with a felony. The law does not require that the threat be credible. ProPublica and WPLN previously reported that an 11-year-old boy with autism denied making the threat during class and was later arrested by Hamilton County sheriff’s deputies during a birthday party.

Advocates warned Tennessee lawmakers during this year’s legislative session that the law would be particularly harmful to students whose disabilities make them prone to frequent verbal abuse and disruptive behavior.

Lawmakers included an exception for people with intellectual disabilities. In addition to autism, Ty has an intellectual disability as defined by Tennessee law, according to psychological reports from Ty’s mother and the school district. But the family’s attorney said there is no evidence that law enforcement considered that or investigated whether Ty was impaired before handcuffing and arresting him.

The law does not specify how police should determine whether a child has an intellectual disability before filing charges. Rep. Cameron Sexton, speaker of the Tennessee House and a Republican co-sponsor of the law, said Tye’s case “may require more training and resources” for school officials and law enforcement. He said that it shows that.

Rep. Beau Mitchell, D-Nashville, a co-sponsor of the bill, said he hopes the exemption for children with intellectual disabilities will be enough to prevent arrests of students like Ty. said. “No one passed that law so that children with any type of disability could be prosecuted,” he said.

But he said the law was still needed to prevent the threat of misinformation that disrupts learning and terrorizes students. “I don’t know whose level of trauma is the greatest: the kids in the classroom who wonder if there’s an active shooter roaming the hallways, or the kids who don’t know better and get arrested for saying things like that. ” Mitchell said. “It’s a no-win situation.”

The state does not collect information about how the felony law, which took effect in July, applies to children with disabilities like Ty. Hamilton County data provides limited information. In the first six weeks of the school year, 18 children were arrested for threatening gang violence. One-third of them have a disability, which is more than double the district’s overall percentage of students with disabilities.

Before the new school year started, Ty’s mother sent an email to school officials asking for help in making her son’s transition to eighth grade as smooth as possible.

Ty’s professional education plan says he is outgoing and friendly with other students, but his disability often causes him to become verbally abusive and disruptive in class. He struggles to control his emotions when required to follow classroom guidelines and understand social situations and boundaries.

Federal law prohibits the school from harshly punishing him for his conduct because it is caused by or related to his disability. But Ty’s principal then emailed his mother to say that Tennessee’s gang violence and intimidation law requires school officials to report the incident to police.

Ty’s mother said her worst fears came true when she received a call that her son was being arrested. Her son’s autism was misinterpreted as a threat. “I looked in his backpack and there was nothing in there that could hurt anyone, so why handcuff my 13-year-old autistic son, who didn’t understand what was going on?” “Did they take him to a juvenile detention center?” she said.

Disability rights groups said children like Tai should not be arrested under current law. And they sought broader exceptions for children with other types of disabilities.

Tennessee Disability Rights Policy Coordinator Zoe Jameel met with Mitchell before the law was passed and said the law would help children with undiagnosed disabilities who have communication or behavioral difficulties. He explained that it could have a negative impact on children (such as children with developmental disabilities). I have an intellectual disability. She suggested language that Mitchell and other sponsors could include in the law to prevent children with disabilities from being unfairly arrested.

One version of the proposed amendment reads: “A student who makes a threat that is determined to be indicative of the student’s disability shall not be prosecuted under this section.”

The amendment was never voted on in the state legislature. Lawmakers instead passed a narrower version.

“I think this shows a lack of understanding of disability,” Jameel said.

Sexton, the Republican House speaker, said children with disabilities can commit acts of gang violence and should be punished under the law. “I think you can make a lot of excuses for a lot of people,” he said.

Ty still doesn’t fully understand what happened to him and why.

One morning in October, Ty turned his stuffed bunny toward his mother and asked, “Is it his fault you can’t take your stuffed animal with you anymore?”

Ty’s mother told him the reason was because he didn’t ask first. “You can’t sneak things out of the house,” she said.

“Does that bother you?” he asked her.

“Yes, of course,” she said. “Maybe you want me to think it’s a bomb again and take you back to the children’s prison?”

“No,” he said emphatically.

After the incident, a Thai junior high school suspended him for several days. His case was quickly dismissed in juvenile court.

The principal told Ty’s mother in an email that if Ty made a similar comment again, the school would follow the same procedures. She decided to transfer him from Ooltewah Middle School as soon as possible.

“Every time we walk past that school, Ty says, ‘Mommy, are you going back to prison?'” Will you take me back there? ‘He’s really traumatized,’ she said. “I felt like no one at that school was really fighting for him. They were too busy justifying their actions.”

The 11-year-old boy denied the threats and was allowed to return to school. Tennessee State Police arrested him anyway.

Mitchell, a Democratic congressman, said it was “heartbreaking” to hear that Ty was handcuffed and traumatized. But “we’re trying to stop people who should know better from doing things like this. If they do it, they should do more than a slap on the wrist.” There is,” he added. He said he would be open to considering a carve-out of the law to cover a broader range of children with disabilities in future Congresses.

But he said he believes the current law will make all Tennessee children safer, regardless of their disability.

Help ProPublica’s Education Report

ProPublica cultivates a network of educators, students, parents, and other experts who help guide our education coverage. Please take a few minutes to join our Source Network and share what you know.

expand

Source link