Eve here. Among the key findings in this post is that Trump’s trade escalation will lower real wages in the United States. Quell’s surprise! It also includes a useful chart showing estimated effects of the state.

Andres Rodríguez-Clare Mauricio ulate, and Jose P. Vasquez. Originally published on Voxeu

In 2025, the US government announced a series of increased tariffs targeting key trading partners, including Canada, China and Mexico. This column estimates the economic imagination of these proposed tariffs in the US and worldwide. According to this model, real wages in the US fell by 1.4% in 2028, while GDP fell by about 1%, with differences between states. Manufacturing in the US may enjoy a surge in employment, but services and farming employment will decline. Globally, countries that trade more with the US are losing a lot.

Since early 2025, the US government has announced a series of increased tariffs targeting key training partners, including Canada, China and Mexico. As Baldwin and Barba Navaretti (2025) and Eventett and Fritz (2025) pointed out, these measures could potentially be inconsistent with WTO regulations. Most tariff implementation was postponed within days of the announcement, but those targeting China were enacted as planned. In response to China’s retaliation against early US tariffs, the US further raised tariffs on Chinese imports to over 145%, but then returned to 30%.

The immediate market response to the announcement of the release date highlighted its implications. This is because the US dollar refused to affect it (Hartley and Rebucci 2025). While important guidance remains regarding the decisive deprivation of a critical tariff, even some of the published tariffs could promote average US tariffs, which has encouraged US tariffs to levels not seen in decades. Given the important role of international trade in today’s world economy, and especially the retaliatory measures taken by China, this set of tariffs could ignite the biggest trade war in history, at the high and low INCL of Big.

Our paper (Rodríguez-Claretal. 2025) uses state-of-the-art dynamic quantitative trade models to assess the proposed economic concept of tariff increases in 2025. Our frame is important important FEMA. Statewide redistribution of customs duties.

Important US findings: Intensive impact

Our baseline scenario considers a four-year tariff rise, assuming there is no full retaliation or other simultaneous shock from our training partners. The assets were taken away, and real wages fell 1.4% in 2028, with tariffs still in effect in the final year. Higher tariffs partially offset this loss, but GDP will decrease by about 1% by 2028.

Workforce participation and employment have also declined, reaching levels of 0.65% and 1.1% from the baseline in 2028, respectively. Low actual wages will automatically leave the workforce as market work is less attractive compared to home production.

Witness to the stiffness of downward nominal wages. This will generate recruitment for minors that peak at 0.5% in 2029.

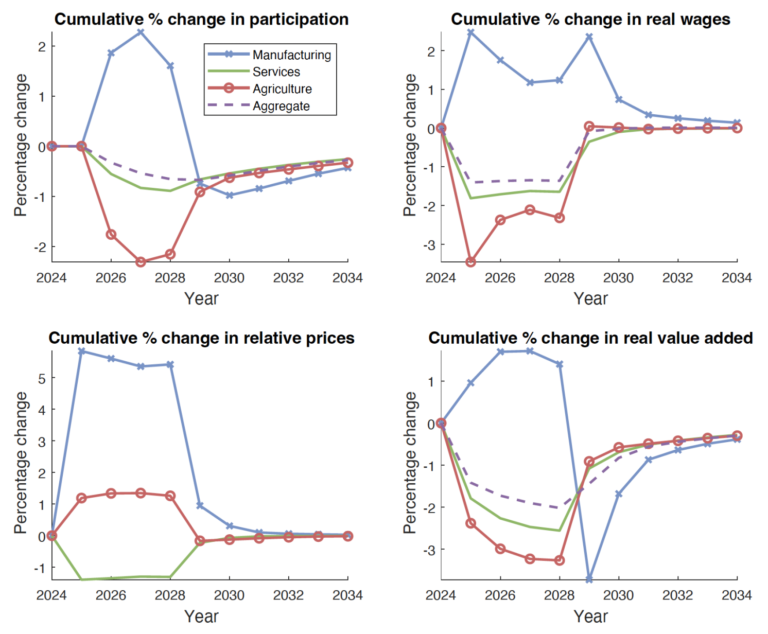

Figure 1. Routes of US related variables on aggrete

Note: Changes in cumulative percentages of (labor supply) since 2024 are in the top left, changes in cumulative percentages of actual wages are in the top right, cumulative change in relative prices are in the bottom left, and cumulative change in actual values are in the bottom right. Manufacturing is a closed blue line, service is a solid green line, agriculture is a red line with circular markers and a dashed purple line, which is aggregate throughout the sector.

Figure 2. Routes of US related variables on aggrete

Note: The left panel shows changes in the cumulative percentage of employment since 2024 (solid green line), changes in the cumulative percentage of labor supply since 2024 (dashed purple line), and unemployment rate of 1% (red line on circular markers). The right panel shows changes in cumulative percentiles in real US GDP (actual income and coined terms) since 2024. Please note that actual GDP includes tariff revenue. The X-axis year is from 2024 to 2045.

Divisional Relocation: Pyrahik’s Wins in Manufacturing

This rate causes substantial reallocation across sectors, and has a significantly different effect on manufacturing, services and agriculture. In manufacturing, which has a substantial US trade deficit, there is a temporary outbreak of employment. At that peak, manufacturing participation will increase by more than 2% as import protection shifts demand for domestic producers.

However, employment in the services sector is declining as the US, a net export of services, faces foreign demand for Lesen. Agricultural employment is also addressing reduced export demand from countries that rented retaliation against the US to address increased input costs from machinery and chemical tariffs. The decline in services and farming employment accounts for a 1.1% loss of employment compared to pre-shock baseline.

Transient dynamics reveal other insights. Once the tariffs eventually return to normal levels, the manufacturing sector faces painful adjustments. Workers who migrated to manufacturing during their protection are facing a collapse in demand. As mentioned above, downloading nominal wage stiffness to prevent long wage adjustments increases employment activity. Consencoly says it benefited most from manufacturing protections during the customs period when its protection was completed.

Uneven burden: state-level splits

An overall 1% decline in US actual GDP masks a major difference at the state level. Our quantification shows that about half of US states experience actual Inome loss, with subs above 3%. State with the biggest losses, including California, Michigan and Texas, show common characteristics. It shows a significant exposure to trade with the most affected countries (particularly Canada, China and Mexico) as it is strongly dependent on a significant risky export industry, and risky risk risk risk.

In contrast, states with trade exposure and economic declines for domestic markets, including Colorado and Oklahoma, perform relatively better. Tosee is more than offset by losses in other regions, but agricultural submarines (such as Nebraska) that succeed in imports (such as Nebraska) even see small profits.

Figure 3 Cumulative changes in real income from 2024 to 2028 were percent across US states.

Note: The darker the blue shade, the smaller the actual imagination (or higher gain).

Global impact

It also quantifies the impact of trade wars on other countries. Naturally, countries that trade more with the United States will suffer huge losses. For example, Canada sees real Inome, Mexico faces a loss of 2.7%, with Ireland’s experience declining by 3%. These countries will withstand even more serious effects than China, where you have a 0.5% loss. The US itself is the US itself, as they are exposed to trade with the US and have a more limited ability to use tariffs to affect the prices of good partners.

Several countries, such as the UK and Türkiye, have actually benefited from the trade war. As the US faces a minimum 10% tariff, these countries will improve access to foreign markets, leading to increased trade below.

Figure 4 shows that Real Incom has fallen across the country by 2028

Note: This diagram shows the percentage of cumulative real Japanese (matching actual GDP) by 2028, across countries. For country abbreviation codes, see Rodríguez-Clareet al. 2025, Appendix B.1.

Sensitivity to important assumptions

Our baseline quantification relies on several important parameters. Most importantly, the resilience of trade governing the way buyers can easily replace between products. Our baseline assumes a standard elasticity of 5, but there is subject-matter inconsistency in the literature regarding the appropriate values used for this parameter. For example, Boehm et al. (2023) estimate the value to be close to 1 for trade elasticity.

The lower the value of trade resilience, the more relative market power the US has to do with smaller training partners and suffer less from tariff shocks (even if other countries retaliate). In fact, if this elasticity is a low value cover (e.g. 0.76), the US experiences a small tally gain of 0.4% of real revenue from the impossible of tariffs.

The extent of retaliation by trading partners also affects the magnitude of US losses. Our baseline quantification assumes 100% retaliation (reflecting increased US tariffs in other countries). However, if the trading partner does not retaliate at all, the actual US GDP loss will be ordered to be 0.5%. Interestingly, foreign retaliation has the unexpected advantage of reducing the boom bust cycle in manufacturing employment. Without retaliation, manufacturing employment increases more rapidly during the protection period, and unemployment rates become more severe once tariffs are over, with a total of 1% reaching 0.5% under full retaliation. This creates a massive manufacturing boom without retaliation that requires nominal wage adjustments when protection ends, and involuntary unemployment due to downward stiffness in nominal wages.

Finally, the period of the trade war is also important in the way it was expressed. Extending the tariffs to 16 to four years will increase the cumulative actual inoma losses from 2024 to last year, with high tariffs being active from 1% to 1.8%. The increased time to adjust and respond to tariff-induced distortions increases overall welfare loss.

Limitations and policy considerations

It highlights three major policy takeaways. First, increasing employment in protective sectors like manufacturing is more than offset by losses in other parts of the economy. Second, there is a geographical dispersal in the exposure to shocks, and therefore, with losses arising from third, the unemployment rate that arises at the end of protection suggests that temporary tariffs create adjustment costs in both directions. During customs, workers own into the protected sector and upon completion of protection, the PSE PSE will displace and put pressure on permanent protection.

It also highlights some limitations of the analysis and leads to underestimating the negative concept of short TRM of shock. First, our framework does not capture the effects that may arise from uncertainty or height increase. There is a geopolitical tension. Second, the model’s comprehensiveness smoothes the effects between agents. Granular models imply larger and more heterogeneous effects across regions and sectors. After hearing these warnings, our quantitative analysis provides valuable insight into how the 2025 tariff shock will spread through US states and the global economy.

See original bibliographic submission